Michael Wassegijig Price

INDIGENOUS ASTRONOMY reflects the connection with nature and constitutes the difference between Western science and indigenous perspectives of the natural world.

Understanding the synchronicity of natural and astronomical cycles is integral to Anishinaabe cosmology and shows us how the Anishinaabe cultural worldview and philosophy are reflected in their celestial knowledge and how indigenous knowledge relates natural phenomena to everyday life.

Adapted from Winds of Change, v17 n3 p52-56 Sum 2002, ISSN-0888-8612.

This and more stories at RevolvingSky.com

I was never so touched by indigenous knowledge as I was during the Naming Ceremony of my 4-month-old son. A highly respected Anishinaabe Elder, Tobasanokwut Kinew, came down from Winnipeg, Canada to do the ceremony. It was a cold day in early March near Bemidji, Minnesota , with blizzard-like conditions and freezing temperatures. I had given him "Asemaa" or tobacco several weeks prior, respectfully requesting the ceremony.

The name that he gave to my son was "Gizhebaa Giizhig," which means "Revolving Sky." The name, Gizhebaa Giizhig, refers to the circular movement of the sky throughout the year. It refers to the circular movement of the sun, moon, stars and seasons.

"Gizhebaa" also refers to people dancing in a circular fashion around the drum arbor at powwows. That mystical movement around a source of energy is reflected in the name of Gizhebaa Giizhig.

This ancient knowledge came from watching the stars move to different regions in the night sky throughout the year and observing the relationship between seasonal changes and stellar movement.

Tobasanokwut said, "If the naming ceremonies are performed as they should be, the teachings, history and culture of our people can be found in the names of Anishinaabe people." The sacred knowledge of the natural world is inherent in the language.

In the weeks following that ceremony, I became obsessed in seeking out the star knowledge of my ancestors, the Anishinaabe people (also referred to as Chippewa or Ojibway). For the first time in my life, I felt a connection to the star world through my son's naming ceremony.

That feeling of "connection" constitutes the difference between western science and the indigenous perspective of the natural world. For me, the star world has a totally different meaning than when I was a college student struggling with the mathematical calculations of physics and astronomy. I believe that this spiritual connection or kinship with the natural world is what defined and sustained Native American communities for thousands of years before the dawn of industrialized society.

The landscape of the Great Lakes region, weather patterns, sun and moon, revolving star patterns, bird and animal migrations are affirmations of who we are, what we believe, why we exist, and how we make sense of the world around us.

Understanding the synchronicity of these cycles, as well as the physical and metaphysical essences of creation, make up the cosmology of the Anishinaabek.

Because stars move from east to west, the Anishinaabe believe that when we die, our spirits travel to "Ningaabii'anong;" the Western sky. The Anishinaabek also believe that new life and knowledge emerge from "Waabanong ; " the eastern sky. Thus, many ceremonies and traditions reflect these cardinal directions. From the Western scientific standpoint, we know that it's not the stars that are revolving, but the earth that is actually revolving. But, this scientific fact is part of the Western scientific paradigm and not part of the Anishinaabek cosmology.

The constellations and star knowledge relate to seasonal changes, subsistence activities, ceremonies and storytelling of the Anishinaabek. Seasonal changes correlate with the movement of stellar constellations, which, in turn, are reflected in tribal stories and ceremonies.

Anishinaabek Constellations

The constellations and star knowledge relate to seasonal changes, subsistence activities, ceremonies and storytelling of the Anishinaabek. Seasonal changes correlate with the movement of stellar constellations, which, in turn, are reflected in tribal stories and ceremonies.

All knowledge is interconnected. The Anishinaabek, keen observers of cosmological and ecological relationships, evolved traditions and ceremonies from this knowledge.

Knowledge was generally passed down through the "Midewiwin," a society of healers and spiritual leaders, or the "Waabanowin," the Society of the Dawn. Today, college and university level curricula integrate this knowledge at tribal colleges across the country. The sacred teachings and ceremonies of the Anishinaabek are still reserved for the "Midewiwin."

Hole in the Sky

The Anishinaabe constellation, "Bugonagiizhig Hole in the Sky," is the star cluster known as Pleiades. The seven stars represent the opening between the Earth and the star world. This "Hole in the Sky" leads to the spirit world. "Bugonagiizhi," is a winter constellation that rises in the northeast sky in October and makes its way across the winter sky, sinks below the northwest horizon in late March, becoming invisible from April through August.

These seven stars also represent the seven poles used in the construction of the "Jiisakaan Shaking Tent Ceremony." Other Anishinaabek communities refer to Pleiades as "Madoo'asinug Sweating Stones." The seven stars in this constellation represent the seven stones used in the sweatlodge ceremony.

The Sweatlodge

The "Madoodiswan," or "Sweatlodge," is the constellation also known as the Corona Borealis. Characterized as a group of stars in a circular pattern with the door of the lodge opening to the north/northeast, it rises in the northeast sky in March and disappears on the horizon in September. The "Sweatlodge" constellation is directly overhead during the early evenings of June, yet is not seen for six months throughout the winter.

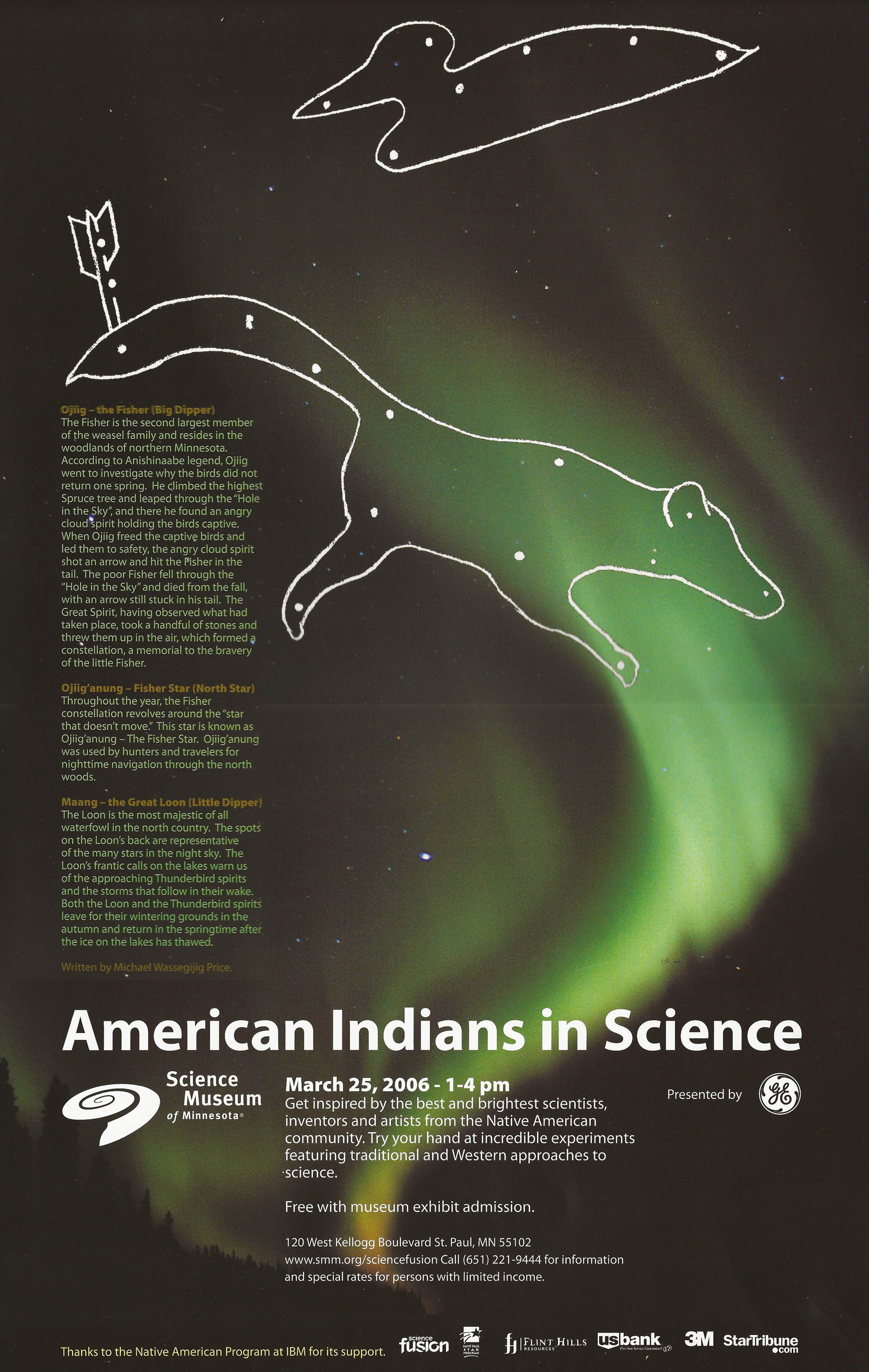

The Fisher

The most wellknown constellation is the Big Dipper or Ursa Major. To the Anishinaabe, the Big Dipper is part of the constellation "Ojiig'anung Fisher Star." "Ojiig'anung" lies just above the horizon from October to December. In December, it emerges in the northeast sky. Throughout the long winter, the Fisher makes its way across the night sky. The Anishinaabek knew that spring was close when "Ojiig'anung" was directly overhead in the early evenings.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1793-1864) had recorded the story of the "Ojiig'anung (The Fisher)," but did not make the connection between the story and the rise of the constellation in early spring. The rise of "Ojiig'anung" was also an indication that it was time to prepare for "Aninaatig ozhiga'igewin tapping of the maple trees."

Cliff Paintings

Carl Gawboy, an Anishinaabe artist from the Bois Forte Reservation, suggested that some of the cliff paintings found at Hegman Lake and on the shores of Lake Superior are actually star constellations. This knowledge came through his father and grandfather. Gawboy points out several rock paintings that can be mapped out in the star world: The Fisher, Great Panther, Sweatlodge, Wintermaker and Moose.

The Great Lynx

"Mishi bizhiw," or the Great Lynx, is another constellation that emerges in the late winter skies. Because the lynx is known to be a somewhat dangerous animal, this constellation is a reminder that the north woods, especially during the transition time between winter and spring, can be dangerous. Thinning ice on the lakes and rivers, hard crust on the snow, flooding, and unpredictable snowstorms are characteristic of the Great Lakes region during this time.

The constellation, "Mishi bizhiw," consists of the two constellations of Leo and Hydra. The head of Leo makes up the long curled tail, while the head of Hydra makes up the head of the Great Lynx.

The Loon and the North Star

Polaris, or the North Star, is known as "Giwedin'anung Star of the North." "Giwedin'anung" was used in determining the four cardinal directions as well as navigating through the Great Lakes region at night. "Giwedin'anung" is part of the constellation known as "Maang The Loon." The Loon constellation comprises the stars of the Little Dipper. "Giwedin'anung" is located at the tip of the tail feathers of the Loon constellation.

The Milky Way

According to the Dictionary of the Ojibway Language (1878) by Frederic Baraga, the Anishinaabek word for Milky Way is spelled "tchibekina." I had asked several Elders in the area what that word meant, but no one knew. Finally, George Goggleye, an Elder from the Leech Lake Reservation, said that Baraga had spelled it wrong. It was actually pronounced "jiibay kona" (jiibay spirit; konapath), which meant "Spirit Path."

The rock pictographs at Hegman Lake in Canada, which show three canoes traveling in the same direction, may indicate the "jiibay kona" or Milky Way. Carl Gawboy believes that, since there are no star patterns that exhibit three canoes, the pictographs actually represent spirits traveling the "spirit path" in celestial canoes. The Milky Way was believed to be the path that spirits followed to the spirit world after death.

Many tribal traditions and stories originated from actual observations that occurred centuries ago, but are still preserved in tribal oral traditions.

Catastrophic Events from the Star World

In his book, Red Earth, White Lies, Vine Deloria, Jr., Hunkpapa Lakota, stated that natural and catastrophic events throughout the Earth's history and within the time frame of human memory, are contained in tribal stories and traditions. Many tribal traditions and stories originated from actual observations that occurred centuries ago, but are still preserved in tribal oral traditions.

The One Who Came From a Shooting Star

Tobasanokwut Kinew told me the story of the wolverine and the shooting star. The Anishinaabe word for the wolverine is "Gwiingwa'aage" which means "The One Who Came from the Shooting Star."

There were four star spirits soaring through the night sky. One of the four spirits was belligerent and illtempered. While soaring through the night sky, the contentious star spirit, in an attempt to startle and scare everyone on Earth, flew too close, lost control, and collided with the Earth.

The spirit left a huge crater in the Earth where it hit. The Anishinaabek, who were familiar with the antics of that particular star spirit, cautiously xamined the crater and continued to observe it for several years. Over time, it filled with water and became a lake. Eventually, trees and grasses began to grow on its banks.

One day, an unusual animal emerged from this lake; an animal that the Anishinaabek had never seen before. It had a vicious and ill-tempered disposition. It was said that this animal was the star spirit that hit the Earth long ago. So, the Anishinaabe called this animal "Gwiingwa'aage" ("Gwiingwa"shooting star; "aage"originating from). Contained within the Anishinaabename for the wolverine is the occurrence, recorded in oral tradition, of a meteorite colliding with the Earth long ago. That crater still exists today in northwestern Quebec, Canada.

The Long-Tailed Heavenly Climbing Star

The story of "Genondahway'anung" is an account of an astronomical event that was recorded within the oral tradition of the Anishinaabek as told by Fred Pine, an Anishinaabe Elder from Garden River First Nations, near Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

In the story, "Genondahway'anung Long-Tailed Heavenly Climbing Star" hit and scorched the Earth long ago. The Great Spirit, "Gchi'Manitou," warned the Anishinaabek ahead of time about the approaching star, and so they fled to a bog and rolled themselves up in the moss and mud to protect themselves.

The Anishinaabek who maintained their spiritual beliefs heard the warning of "Gchi'Manitou." When the star hit, its fiery tail spread out over the entire landscape. Nothing survived the heat. The giant animals and trees were all killed off. Only those Anishinaabek who rolled up in the moss and mud lived to tell this story.

This catastrophic event cannot be dated exactly, but may have possibly coincided with the Great Firestorm of 1871, which was caused by fragments of the tail of Biela's Comet disintegrating over Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois. In 1832, Beila's Comet, on its orbiting path, just missed colliding with the Earth by one month.

Because of the close proximity with the Earth's gravitational field, Beila's Comet split into two trajectories and became two comets approximately 16,000 miles apart. The comets were observed in 1839 and 1846, but suddenly disappeared. It wasn't until October 8, 1871, that the simultaneous firestorms broke out across the upper Midwest.

The fall of 1871 was particularly dry which made vegetation vulnerable to fire. Because the Earth passed through its orbital path, scientists theorized that the fires were caused by debris from the disintegrated tail of Beila's Comet. Witnesses in Peshtigo, Wisconsin made mention of "fire coming from the heavens." The story of "Genondahway'anung" resembles the events surrounding the mysterious conflagration.

The stories of "Genondahway'anung" and "Gwiingwa'aage" also resemble the Tunguska Blast of 1908, where a meteorite crashed into the Tunguska River region of Siberia, Russia. The Tungus tribes people, an indigenous group in Siberia, and some Russian fur trappers witnessed the gigantic fireball with its long, fiery tail just before it impacted the Earth. The blast incinerated and leveled an area approximately 1,240 square miles. Trees were felled in an outward direction from the epicenter of the crater.

Afterwards, witnesses recalled "black rain" in which airborne ash and debris from the blast mixed with the rain. Shockwaves, through the Earth's crust, pulsated approximately 620 miles in all directions.

Halley's Comet

Halley's Comet, the brightest and most spectacular of all comets, becomes visible on its orbiting path every 75 years. The Anishinaabek at Garden River First Nations have recorded accounts within their oral history of Halley's Comet in 1834 and 1908. There are several names among neighboring Anishinaabek communities for Halley's Comet, which include: Gitchi'Anung ( Great Star), Wazoowaad Anung (long-tailed star) or No'aachiigay Anung (prophecy star).

The story of the Halley's Comet, the Prophecy Star, tells that when nature comes out of balance and people lose their spiritual path and purpose, a star spirit would return and destroy the earth. In 1994, when scientists observed the Shoemaker-Levy-9 Comet crashing into the southern hemisphere of Jupiter, it was now apparent to the scientific community that the Earth is vulnerable to collisions with comets or asteroids of apocalyptic proportions.

The story of the "No'aachiigay Anung," reminds Anishinaabek of this fateful and potential reality through tribal oral traditions.

Even though the scientific understanding of the stars and planets is exact and empirically measured, it has little to no relevance to those who have not engaged the discipline of astronomy.

As I learn more and more, I am realizing that indigenous knowledge not only describes natural events and phenomena, but also it relates that knowledge to our everyday lives as Native Americans.

Through my son's naming ceremony, I am connected to the celestial movement of the heavens. By knowing the constellations, the teachings and ceremonies of my ancestors are presented with each season. It is my hope that this star knowledge is revitalized in our communities, so that one glance in the night sky will reveal the cultural worldview and philosophy of the Anishinaabe people.